In the New York Arunachala Ashrama, on Monday morning, April 10th, 2000, Arunachala Bhakta Bhagawat looked as if he were asleep. On closer examination it was found that his life breath had left the body and he had left with it. From all appearances no one could have guessed that he was about to depart. The previous night he was quietly absorbed listening to both the morning and evening Veda Parayanas, one after the other, then had a meal, smiled and conversed with the Ashrama friends who had gathered that night, but showed no signs that this was his final night.

Since suffering a stroke eighteen months earlier he had been unable to walk and, of course, was weak. He would routinely sit in a wheel chair for five hours every day and, although functioning in a limited way, he was hardly conscious of his frailty, occasionally forgetting that he was unable to walk. Nevertheless he remained ever cheerful and grateful, rarely asking for anything other than a warm blanket and to be helped into bed when he was tired.

Since suffering a stroke eighteen months earlier he had been unable to walk and, of course, was weak. He would routinely sit in a wheel chair for five hours every day and, although functioning in a limited way, he was hardly conscious of his frailty, occasionally forgetting that he was unable to walk. Nevertheless he remained ever cheerful and grateful, rarely asking for anything other than a warm blanket and to be helped into bed when he was tired.

“It is now fifty years since Bhagavan’s Mahanirvana,” was the last thing he was told before he fell asleep and the lights were dimmed. He nodded his head, closed his eyes and that was it. We will never look at him who affectionately watched over us through those kind eyes again. Little did we know then that on April 14, exactly fifty years to the day, we would be cremating Bhagawat’s physical remains.

Once he told us, “Who knows, this body may go any day. What do I have to show for all these years? What will I leave behind? ‘Have I stopped serving, loving and worshipping all of you?’ Everyday I question myself thus and that is what I want you to remember when this body goes.” That was not his dying message to his friends, but was said twenty-five years earlier. It was what he wanted us to remember, and it is not difficult to remember this now, for all through the succeeding twenty-five years he continued to demonstrate his intense love for all of Sri Bhagavan’s devotees who made their way to the Maharshi’s tiniest of abodes in the West, Sri Arunachala Ashrama.

He knew that the love that flooded his heart came to him by the blessings of his Guru, Sri Ramana Maharshi, and as that flood inundated his heart it would overflow in such measure that he longed to deluge the entire creation with it. “You are all Sri Bhagavan for me,” he would say. He never tired of serving devotees and expressing the joy and happiness that filled every pore of his body.

But from all appearances, his ascent on the royal road to realization was not an easy one. Although endowed from birth with a deep faith and natural devotion he had to struggle at every step, beginning with extricating himself from the quagmire of illiteracy and stagnation in his village. Let us read his own words on this matter:

“My mother Srimati Pancha Devi, and father Sriman Girivar Roy, although illiterate, were a very religious and God-fearing couple. I was their youngest child and was brought up in the hope of being given a formal education so that I might be able to read and recite the religious epic poem Ramayana of Goswami Tulsidas, the immortal saint-poet of the Hindi language. Thus, my Lord, Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi, inspired my parents to name me ‘Bhagawat’ (a devotee of the Lord) and to put me under the care of the village teacher, so that I might read and learn about the world.

“From my earliest childhood I remember being given to contemplation and very serious and deep conversation. That is why the villagers often called me ‘an old man in the body of a child,’ and I can picture myself as I used to go about the village with a serious countenance and deep purpose.

“My village was in the backwoods, devoid of even a place of worship. India is a land of God-intoxicated people, and it is very strange that this village could not even build a temple for its residents. To reach my village one had to make a great effort. No road led to it and all of us had to walk through fields, farms, floodwaters and sun-baked lands, and there was every likelihood of losing one’s way in the night.”

Even before reaching the age of ten Bhagawat became active in the Non-Cooperation movement of Mahatma Gandhi. This may have disconcerted his older brothers and parents, but Bhagawat was an incorrigible idealist right from his youth. Any high ideal outside the normal pursuits of life invariably captivated his heart and mind and he would throw his whole being into it with the utmost sincerity and intensity. It happened again when he read the life of Gautama Buddha in upper primary school. As a teenager his motto became, “National Liberation and Self-realization.” His zeal for independence landed him in prison when he was seventeen years old.

His education was interrupted. In spite of financial difficulties, Bhagawat’s family was still keen to send him for higher studies. After his release from jail he completed his high school in Calcutta, and then attended the Varanasi Hindu University and finally completed his B. A. at Patna University in Bihar. He then took employment as a teacher in a Hindi school in Darjeeling, a Himalayan hill station. It was here, about a month before his 29th birthday, he first read the Hindi version of A Search in Secret India. The moment his eyes fell on the photo of Sri Maharshi he wanted to fly to his abode at Arunachala.

He writes: “Near around 10th October, 1941, I received the book Gupt Bharat Ki Khoj, a Hindi translation of Paul Brunton’s book, A Search In Secret India. I did not know about the book, but had simply come across an advertisement of it in a Hindi magazine. I must have been drawn towards it because it contained the stories of seers and sages of India. From the moment the book landed in my hands I was glued to it, and on finishing it, decided to go down to South India to have darshan of Bhagavan Ramana. I was also at that time instinctively drawn towards astrology and was very much impressed with the description in the chapter “Written In The Stars.” As it turned out, I went to Ujjain to learn astrology, instead of going to Arunachala for Bhagavan’s darshan.

“Although I spent some time in Ujjain and applied myself to astrology, I never wavered in my devotion to Bhagavan Ramana and tried my best to draw the attention of my teacher to the wonderful Sage who was radiating His Grace from Arunachala. With my mind’s eye I saw Bhagavan sitting in Arunachala and looking at me. He was pouring His Grace on me, but He did not make it possible for me to go to Him. Instead, I pursued the study of astrology.”

Because Darjeeling was considered a security-sensitive area by the British, Bhagawat was not permitted to return there to teach. The authorities had discovered his record of political activity. He then channeled his energy into Gandhi’s Quit India Movement, but being hard pressed for income took several jobs as a journalist with newspapers in Ujjain and Calcutta.

As an idealist, Bhagawat was always inspired by the American Independence movement of the 18th Century and the purest forms of American democratic ideology. A longing in his heart arose to travel to the “New World,” even though he had no contacts in the West or financial means to make the journey. He somehow intuitively felt his future was linked to America and no one could dissuade him from this apparently impracticable dream. Only his sister encouraged him by saying, “I do not know where you will find the money to go to America, or how you will do it, but you are so intent on going, so sincere in your desire, I believe God will make it possible for you to go.” And he did go—in 1947, the year India attained independence.

He received a fellowship from the University of Iowa and a sympathetic friend arranged to lend him the money to make the ocean journey.

After two years in Iowa he received a Masters degree in journalism and began a job as the Information Officer at the Indian Embassy in Washington, D.C.

In accordance with the prevailing custom in India, Bhagawat was married to Yoga Maya Devi when he was just a boy of 17. She was only 8 at the time. Because of his constant moving about for education and to procure an income during his early years, he was unable to stay with her for any lengthy period of time. She joined him in the U. S. only in 1952. They gave birth to their first child in 1953. It was the following year that Bhagawat experienced a dramatic surge in his inner life:

“On Wednesday, October 13th, 1954, I was in the guest cottage of a Quaker couple, Helen and Albert Baily Jr., located on their farm in West Chester, Pennsylvania. The cottage was situated in a valley near their residence. On the second floor of the cottage my wife, Yogamaya, our 15-month-old boy, and I were occupying the large wooden-framed bed that night. In the second half of the night I saw Bhagavan Ramana sitting on the bed near my head. Although this was a dream, I saw it as clearly as I see the sun during the day, and remember it vividly. His famous figure was near my head and His legs were dangling. Arunachala Shiva Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi stayed near my head for quite a while so that I could drink deep in Him. Bhagavan simply kept on looking at me and I was filled with joy and happiness and could not turn my eyes away from Him. I do not know how long this lasted. But once I woke up I could not return to sleep and sat on the bed meditating on Him. All morning and day I kept on thinking of the darshan Bhagavan had given me in my dream….That dream enabled the sugar doll to be dissolved into the Divine Ocean of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. Since then I have not been the same Bhagawat I used to be.”

The following night he had another stirring dream wherein he saw the Sanskrit word “Upanishad” written on a loose leaf. Then the leaves of text begain to turn one by one until he woke.

These experiences rekindled the fire of devotion to Guru Ramana that was first sparked in 1941. Though the Maharshi had left his body four years earlier, Bhagawat began writing letters to him at Sri Ramanasramam, as he was beginning to experience him as a living Presence.

On an invitation to teach in Iowa, Bhagawat resigned from the Indian Embassy in 1957. The teaching position did not materialize and he looked elsewhere for employment. He thought he might teach in a U. S. college, write books and travel. But no promising offers came. He inwardly felt that his Master, Sri Ramana, was removing all worldly ambitions from his mind and was steadily pulling him deeper into his spiritual center for sustenance.

In 1959, Bhagawat, with his family returned to India. Now He was able to fulfill his long-cherished dream of visiting Ramanasramam in Tiruvannamalai.

“We returned to India in February, 1959. We lived in my village and the world of cold, corrugated, cement and concrete was replaced by the village life. We were completely destitute in the true sense of the term. It was a very trying period for all of us. But the Grace of Bhagavan kept surging inside me and was the main sustenance of my life. The desire for the darshan of Arunachala Ramana at Sri Ramanasramam remained unquenched within me because I had no money to travel. At about this time, Rambahadur, my nephew, was inspired to visit Arunachala and he invited me to accompany him to Sri Ramanasramam in Tiruvannamalai, South India.

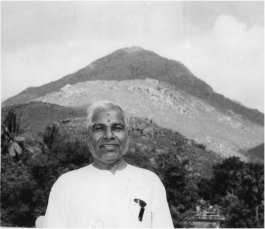

“As soon as we caught the first glimpse of Sri Arunachala, I was swimming in the Bliss of Bhagavan. After 19 years Bhagavan had brought me to His Lotus Feet. The greatest dream of my life was fulfilled.On December 30th, 1960, Friday morning, Rambahadur and I were in Sri Ramanasramam.

It was here at Sri Ramanasramam that Arthur Osborne, a staunch devotee, author of several profound books on Bhagavan and founder of the Mountain Path magazine, encouraged Bhagawat to start some regular meetings in the U. S. centered on Sri Maharshi when he returned. Bhagawat did not know for sure at that time he would return, but he did, taking up a position at the Indian Mission to the United Nations in New York City in 1962.

In 1965, Bhagawat, reflecting on the recent events of his life, writes: “Bhagavan made it possible for me to find employment once again in the United States. But New York was the last place we wanted to live. In spite of my best efforts to get away from New York, Bhagavan held me here. He must have some purpose in not helping me find employment elsewhere.”

The purpose would soon reveal itself. On November 12th, 1965 Bhagawat began weekly meetings in a room at the American Buddhist Society on the West side of Manhattan. He wanted it to be a meeting place for sincere aspirants who wished to deepen their spiritual lives in the light of the Maharshi’s guidance and grace. In 1966, Arunachala Ashrama, Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi Center was incorporated and registered as a charity with the state and federal governments. With the renting of a meeting room at 78 St. Marks Place in 1967, the weekly meetings became daily. In 1969 the Ashrama moved to a rented storefront on 342 East 6th Street, near First Avenue and remained there for the next seventeen years.

Bhagawat’s dream for a country residential Ashrama was realized in 1972 when the Nova Scotia, Canada, Arunachala Ashrama was founded at the foot of the rolling hills of the Annapolis Valley.

All along Bhakta Bhagawat would emphasize to all visitors the need for spiritual practice. He would say, “This is Arunachala Abhyasa Ashrama.” Abhyasa means ‘spiritual practice.’ Pointing to Sri Bhagavan’s photo, we would often hear him repeat to new visitors, “He teaches and we practice. He has made me His servant and servitor, His doorman and doormat”

He was now consumed day and night, dedicating all his time and energy to the Ashrama and the constant remembrance, or “Self-abidance” as he would call it. He behaved like a man possessed, living from moment to moment, acting on whatever inspiration entered his heart. Intuition and inspiration where the forces that now motivated his life. The intellect and self-will were losing their hold and his life began to take its commands from that inner voice spoken by the Lord of his Heart. “I wander about like a drunken person who does not care what the world thinks of him, as he is oblivious of the physical world in his inebriated state…” He wrote in 1966.

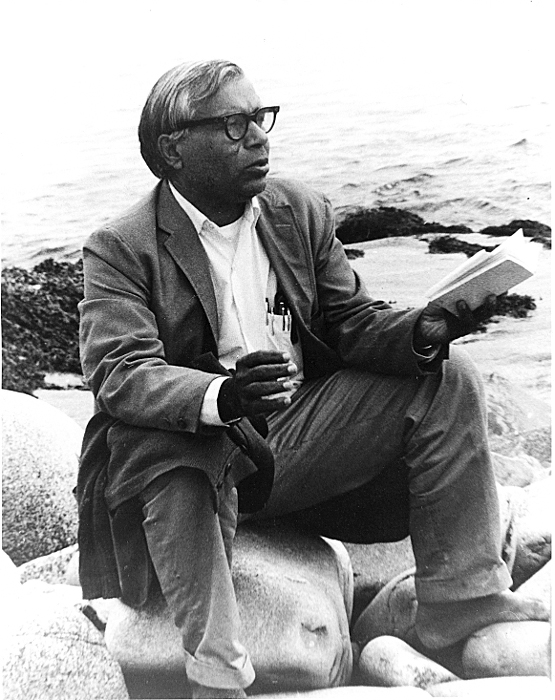

Bhagawat was a prolific writer. He would say, “Unless my mind sinks into the Heart, I cannot write.” And it would sink, and the writing went on and on. All his spare time would be occupied with “Worshipping at the altar of Hermes 3000 [typewriter] with the fruits and flowers of my breath.” He would be seen either sitting inwardly absorbed in front of the typewriter or outwardly absorbed typing thousands of pages of what he called “Prayer Manuscripts.”

In 1970, he began writing a piece titled, “Bhagavan! Thou Art the Self” This went on for 3,500 pages. “From the top of my voice I declare to the world that Thou art the very breath for me and day and night I find myself immersed in the surging Ganga of the Silent Sage of the Holy Hill of the Beacon Light, Sri Arunachaleshwara Shiva Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi…” Thus he writes on the last page in 1973, only to begin another piece titled, “Bhagavan! Thou Art My Breath.” He would never read what he wrote unless asked to. He would make many carbon copies, and when the Xerox machine hit the market he was the most diligent of customers. He would ask us to send copies to this or that person, thus fulfilling, in his own unique way, the desire to share whatever grace and experience Sri Ramana had blessed him with.

“Openness of Heart” was a favorite expression of his. “Guilessness, humility,” he would of say, “these are the essential qualities of an aspirant.” He longed for the pure company of those rare souls who embodied these qualities. He would travel any distance at any time of day or night to benefit from serving and associating with such friends. “I need your company more than you need mine,” he would tell us. And he believed it, though we certainly thought otherwise. In him we found a devotee on whom Sri Ramana Maharshi had showered his grace in full measure. He experienced his living Presence both within and without, and like us, had never seen Sri Bhagavan in the body. Bhagawat provided us with an example of how to gain the Master’s grace and attain the purpose of human existence in the light of the life and teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi.

Bhagawat was a man who could inspire and mold seekers into genuine devotees. “In Sri Bhagavan’s Ashrama, I have never been able to say anything unless I have realized it first in my own life.” Those few who could see into his pure heart had little trouble benefiting from his guidance and love. He was a married man with a son—he would never say ‘my’ son but ‘our’ son. Because of his sometimes impractical idealist way of life he regretted that his family had to suffer. When his wife became blind from diabetes Bhagawat served her with tender kindness and love. During this period someone once asked him what he was doing with his life. He replied with deep feeling, “I serve Mother.” She predeceased him by three years.

Few who had met him during the last ten years of his life could realize his inner state. He would keep silent most of the time, inwardly absorbed. The Heart was everything for him. He would often tell us, “Watch wherefrom the breath rises; it is the Heart. Watch wherefrom the sound rises; it is the Heart. Watch wherefrom the ‘I’ rises; it is the Heart.”

Bhagawat loved books that were divinely inspired, but often had much difficulty reading them. “Words from these books are like the keys that open the door to the Heart, but once the door of the Heart is open, what is the need of a key?” he once asked. Sometimes he would pick up one of the Maharshi’s books or the Tulsidas Ramayana, read a few passages, put down the book and resume his absorption in the Heart.

Occasionally he would call us at odd hours of the night while in ecstatic moods. His desire was to somehow convey it and share with us, but being unable to pull out any words from a mind totally immersed in the ocean of peace and joy he would remain silent and weep. Only after several minutes of cajoling could we get him to utter a single word. We will not get calls like this anymore. We will not see the “man from the village” whose inner luster was hidden from the world by an uncommon simplicity and humility. His intense, unwavering devotion carried him to the heights of inner freedom and joy. Yes, we will not see him again, but what he has given his few friends will not be lost either. He will live with us just as before and we will strive to continue the work he was inspired to begin right here in the “heart of the New World,” New York.